A groundbreaking new biography of Æthelstan marks 1,100 years since his coronation in 925 AD, reasserts his right to be called the first king of England, and explains why he isn’t better known. It also highlights his many overlooked achievements. The book’s author, Professor David Woodman, is campaigning for greater public recognition of Æthelstan’s creation of England in 927 AD.

The Battle of Hastings in 1066 and the signing of Magna Carta in 1215 are two of the most significant moments in English history. However, few people are aware of what transpired in 925 or 927 AD. Professor David Woodman, author of The First King of England and based at the University of Cambridge, is eager to change this narrative not just through his book, but also by advocating for a proper memorial for Æthelstan, England’s first king, who has been unjustly overlooked.

“As we approach the anniversaries of Æthelstan’s coronation in 925 and the birth of England itself in 927, I want his name to be more widely recognized. He truly deserves this acknowledgment,” states Woodman, a professor at Robinson College and Cambridge’s Faculty of History.

Woodman is collaborating with other historians to create a memorial for Æthelstan, which could take the form of a statue, plaque, or portrait in significant locations such as Westminster, Eamont Bridge (where his authority was acknowledged), or Malmesbury (where he was buried). He is also advocating for Æthelstan’s history to be included more regularly in school curriculums.

“There has been so much attention paid to 1066, the moment when England was conquered. It’s about time we reflect on its formation and the individual who unified it,” says Professor Woodman.

Why isn’t Æthelstan better known?

In his book published by Princeton University Press, Woodman attributes Æthelstan’s lack of fame to poor public relations. “Unlike his grandfather, Alfred the Great, who had the Welsh cleric Asser as his biographer, Æthelstan didn’t have anyone promoting his legacy,” says Woodman. “Shortly after Æthelstan’s death, a wave of propaganda helped make King Edgar famous for church reforms, overshadowing Æthelstan’s earlier contributions to education and religion.”

Some historians have dismissed Æthelstan’s claim to be England’s first king because the kingdom fragmented soon after his death in 939. However, Woodman disagrees with this standpoint.

“Just because things fell apart after Æthelstan’s death doesn’t negate his role in creating England,” he asserts. “His innovative political ideas and efforts to unite the English kingdom were remarkable, considering it is surprising that the kingdom lasted as long as it did. We must recognize that his legacy influenced kingship for generations.”

Woodman provides extensive evidence to restore Æthelstan’s reputation.

Military Success

“Æthelstan was incredibly strong militarily,” Woodman explains. “He needed to be tenacious to expand and defend his kingdom.”

A major challenge came from Viking settlements in the north and east. In 927, Æthelstan gained control over the Viking stronghold at York, becoming the first to govern an area recognizable as ‘England’.

As he expanded his territory, Æthelstan also included Welsh and Scottish kings in his royal gatherings. Surviving original documents, preserved in the British Library, showcase the many nobles he commanded to attend. These assemblies must have been grand, involving hundreds of participants.

“The Welsh and Scottish kings must have resented being drawn out of their lands,” Woodman says. “An incredible poem from the tenth century, The Great Prophecy of Britain, even calls for the English to be slaughtered. It may have been a direct reaction to Æthelstan’s growing power.”

In 937, Æthelstan famously defeated a formidable Viking coalition at the Battle of Brunanburh, which involved Scots and the Strathclyde Welsh intent on dethroning him.

“Brunanburh should be as renowned as the Battle of Hastings,” Woodman insists. “Every major chronicle from England, Wales, Ireland, and Scandinavia noted this battle and its significant outcome. It was a watershed moment in the history of the newly-formed English kingdom.”

Woodman believes the battle occurred at what is now Bromborough on the Wirral. “That location makes strategic sense and fits the name’s etymology,” he adds.

Revolution of Government

Woodman argues that Æthelstan’s most enduring legacy lies in his “revolution of government.” The legal documents from Æthelstan’s reign give insight into the type of ruler he was.

“King Alfred must have inspired his grandson,” Woodman notes. “Æthelstan truly understood the importance of the king legislating, and he took crime seriously.”

Once Æthelstan established the English kingdom, royal documents known as ‘diplomas’ evolved from being short and straightforward to elaborate assertions of royal authority.

“These documents were written in a more sophisticated script and sophisticated Latin, filled with literary devices like rhyme and alliteration,” Woodman explains. “They served to showcase his successes.” Moreover, government efficiency improved during Æthelstan’s reign; law codes were distributed across the kingdom and reports were sent back regarding their effectiveness.

“We even see evidence of centralized management in the production of royal documents, with a royal scribe assigned to oversee their creation. This scribe traveled wherever the king and royal assembly went,” Woodman clarifies.

He highlights that while much of Europe fragmented, Æthelstan successfully united England through strategic marriages into continental royal families.

Learning and Religion

Woodman claims Æthelstan reversed the educational decline caused by Viking invasions. “He was intellectually curious, attracting scholars from across Europe to his court,” says Woodman. “He was a great supporter of the church.”

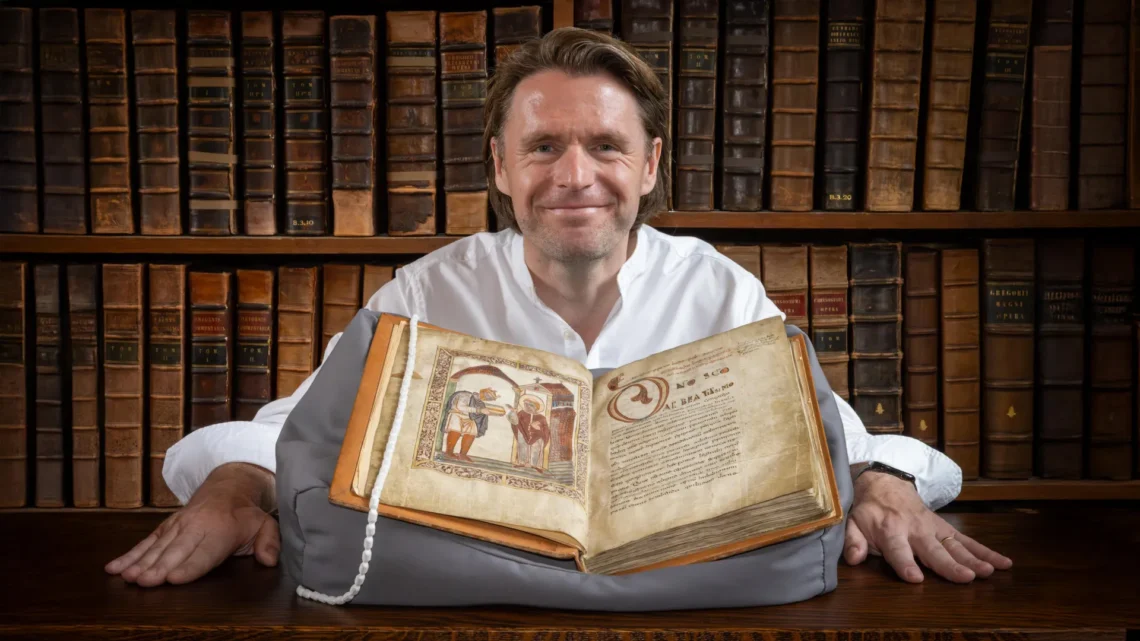

Two pieces of evidence particularly resonate with Woodman regarding Saint Cuthbert. The first is the earliest surviving manuscript portrait of any English monarch, found in a 10th-century manuscript at The Parker Library, Cambridge. Æthelstan is depicted humbly before the saint. “This portrait is one of the most significant images in English history,” Woodman insists.

The manuscript was originally intended as a gift for the Community of Saint Cuthbert and cleverly includes a biography of Mat Cuthbert, seeking to win their favor.

Woodman also felt a deep connection with Æthelstan while examining the Durham Liber Vitae. This manuscript lists prominent figures connected to the Community of Saint Cuthbert in alternating gold and silver lettering. “If Æthelstan appears in this manuscript, he should be listed many pages in, however, someone noted ‘Æthelstan Rex’ right at the top. Seeing that was breathtaking. It’s feasible that someone in his entourage made this entry during a visit to the Community in 934, when this manuscript may have been prominently displayed.”

Notes

*The committee is convened by Alex Burghart MP and includes historian-broadcasters Tom Holland and Michael Wood.

Reference

David Woodman, The First King of England: Æthelstan and the Birth of a Kingdom is published by Princeton University Press on 2nd September 2025 (ISBN:9780691249490)

Summary

A new biography of Æthelstan focuses on his largely unrecognized role as the first king of England, marking the 1100th anniversary of his coronation. Author Professor David Woodman aims to raise public awareness of Æthelstan’s contributions through a planned memorial and enhanced educational coverage. The work highlights Æthelstan’s military accomplishments, revolutionary governance, and promotion of learning and religion, arguing that his influence is crucial to understanding the foundation of England.