Overview

A multitude of paragraphs in Eleanor Doughty’s Heirs and Graces frequently begin with details like, “Bert was the son of Charles ‘Sunny’ Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough.” This raises an intriguing question: why do aristocrats feel the need to share their domestic nicknames, as if these were the keys to high society? It seems that these monikers are a cultural shorthand, albeit an exclusionary one, offering a glimpse into a world governed by class and tradition.

Why It Matters

At the heart of Doughty’s investigation lies the implicit disdain shown by the aristocracy, who often parade their historical significance while espousing a belief in meritocracy. This juxtaposition leaves readers pondering the legitimacy of their superiority when they attribute importance to seemingly trivial details—like the childhood nickname of a distant relative’s pet. These historical narratives can become so bogged down in personal and genealogical minutiae that they obscure the liveliness of individual characters, transforming potentially engaging stories into a morass of names and titles.

Take, for example, the case of Henry “Master” Somerset, a man notorious for his infidelity. Doughty cites that during a dinner, he named his choice for the greatest man of the 20th century not Winston Churchill, but Bernard Norfolk, simply for his role with the Marylebone Cricket Club. While this revelation might pique interest, the surrounding details about who posed the question and Somerset’s familial connections often feel extraneous and dilute the impact of the story.

Doughty presents Somerset as a figure inflated with a sense of entitlement, detailing anecdotes that highlight his abrasive behavior. One wonders amidst the preservation of aristocratic lineage: where are the stories of those who were happy within these illustrious lines?

Key Takeaways

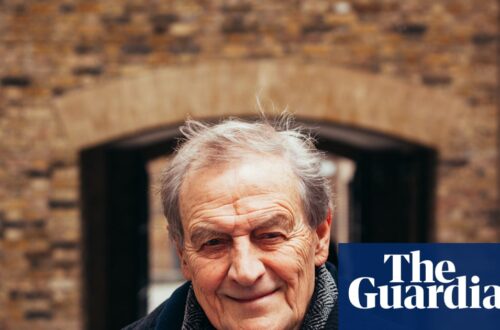

Despite the potential for engaging storytelling, Doughty’s work often feels weighed down by unnecessary details. Each narrative thread is so laden with intricate relationships that they overshadow the essence of the stories being told. Yet, one cannot overlook Doughty’s profound expertise. A former journalist at the Telegraph, where she penned the Great Estates column, she possesses extensive knowledge of the aristocracy’s hierarchy, peppering her writing with enlightening first-hand accounts and rich historical context. Her relentless dedication shines through, making even the most tedious elements of aristocratic history worth exploring.

Final Thoughts

Doughty’s Heirs and Graces presents a nuanced, if sometimes frustrating, look into the complexities of modern British aristocracy. While the narrative occasionally stumbles under the weight of its own detail, the author’s determination to render these historical figures relatable and their stories engaging is commendable. For those interested in the intersection of history and social class, this book offers rewarding insights amid its challenges.