Imagine if all 264 million students enrolled in higher education worldwide formed a country; it would be the fifth most populous nation. About 53% of its inhabitants would be women, with the majority residing in Asia. This diverse population would communicate and study in hundreds of languages, although English would be the most widespread.

The future of universities

This vibrant nation of learners is one of the fastest-growing in the world. Since 2000, the global number of university students has more than doubled, and the amount of students studying abroad has nearly tripled, reaching nearly seven million. Thanks to the Internet and collaborative efforts, the realm of higher education has become increasingly interconnected.

However, this growth is beginning to falter as affluent Western countries become less welcoming to international students. The Trump administration in the U.S. has notably targeted both higher-education institutions and foreign students. As a result, many international students are seeking alternative locations to pursue their degrees, especially in low- and middle-income countries. However, this increased access raises questions about the quality and value of education being provided.

Universities must move with the times: how six scholars tackle AI, mental health and more

These shifts are particularly vital for the scientific community, which relies on universities for training, idea-sharing, and research. “The current global scientific system is facing unprecedented risks to its established strengths,” warns Chris Glass, a higher-education researcher at Boston College.

Experts caution that there is no single narrative that captures the global state of higher education. “There’s never a global story,” Glass states. Nonetheless, he and other scholars have pinpointed major trends in the demographics shaping this ‘country’ of higher education and are forecasting its future.

Here, Nature delves into these trends: the expansion of higher education, particularly in developing nations; the geopolitical influences on and by educational systems; and the implications for who accesses education and what they learn.

Who goes to university?

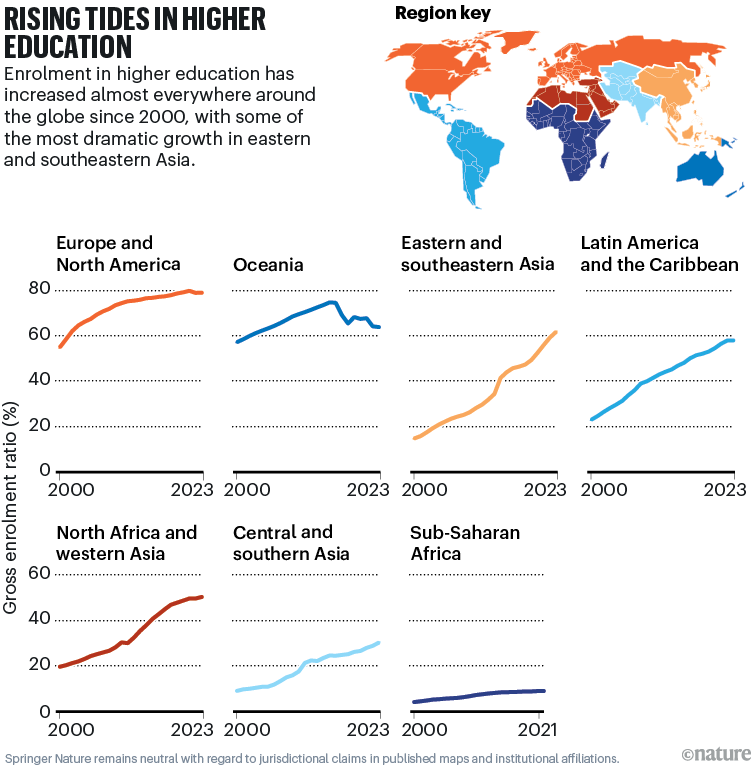

For the past fifty years, one significant trend in higher education has been explosive growth in enrolment numbers. Researchers often measure this growth by comparing the number of enrolled students in a country to its population of school-aged individuals, known as gross enrolment ratio (GER). Sometimes this ratio exceeds 100% because students outside the traditional age group also attend universities.

In Western Europe and North America, attending university has become the norm. The GER in these regions increased from 61% in 2000 to 80% by 2024. In recent years, Central Europe has overtaken them, increasing its GER from 42% to 87% during that time, primarily due to a surge in private institutions following the end of the Soviet Union.

Source: UNESCO

Other parts of the world are catching up too: from 2000 to 2023, eastern and southeastern Asia’s GER rose from 15% to 62%, while Latin America and the Caribbean’s increased from 23% to 58%. Many nations are actively trying to boost their GER. India, for instance, which had a GER of 28% in 2021–22, aims to reach 50% by 2035. The global average GER, which was 19% in 2000, has surged to 44% by 2024.

However, some regions are still facing challenges. As of 2021, Sub-Saharan Africa had a GER of only 9%, an increase from 4% in 2000. It also remains the only region where women are still under-represented in higher education, with about 76 women for every 100 men. Funding is a major hurdle, states James Jowi, director of the African Network for Internationalization of Education. “Most young people can’t afford college tuition,” he explains.

Universities under fire must harness more of the financial value they create

While increasing access to higher education is important, it also raises concerns. Laura Rumbley, director for knowledge development and research at the European Association for International Education, emphasizes that as more people gain higher education, the qualifications needed for good jobs also rise. In regions with high enrolment rates, advanced degrees can become less valuable. “We must ensure higher education opens doors, not closes them,” she asserts.

Where do students go to learn?

With the growth of students and institutions, higher education has become increasingly interconnected globally, but the nature of these connections is evolving.

Researchers refer to these connections as internationalization, indicating how globalization is shaping university education. This is most evident in student mobility. In 2000, 2.1 million students studied abroad; today, that number has grown to 6.9 million, around 2.6% of all students. In the European Union, about 9% of students seek educational opportunities in other EU countries.

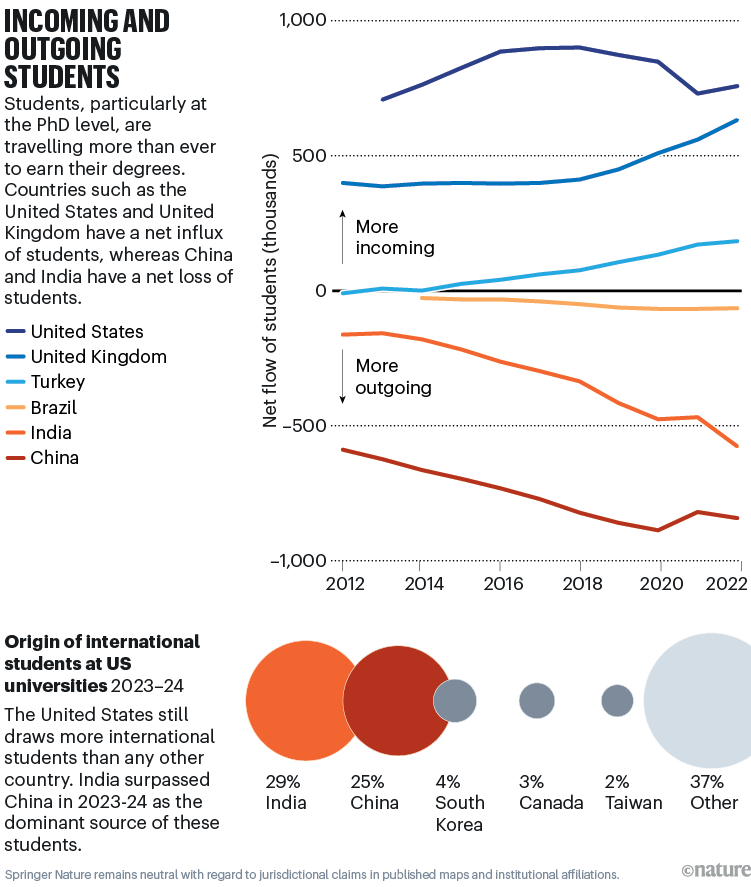

A significant portion of this student mobility comes from postgraduates pursuing specialized education unavailable in their home nations. Generally, these students gravitate towards wealthier countries with robust public education systems. For example, the U.S. has around 20 million higher education students, of whom 1.1 million are international. In contrast, India, with 43 million students, hosts only 46,000 international students (See ‘Incoming and outgoing students’).

Source: UNESCO

Nevertheless, experts predict a possible slowdown in this trend due to two factors: the increasing availability of education in low- and middle-income countries and tightening access in wealthy nations. Countries like the UK, Canada, and Australia have introduced immigration restrictions, which are beginning to reduce enrolment from abroad. Additionally, anti-immigration policies in the U.S. have escalated. The Trump administration has revoked over 1,400 visas, restricted travel from 19 countries, and proposed strict limits on visas for PhD candidates. NAFSA: Association of International Educators predicts a 30–40% decrease in international students in the U.S. by the 2025–26 academic year, costing approximately $7 billion in revenue and 60,000 jobs.

Before the 21st century, the U.S. had a diverse pool of international students from various countries. However, in the past two decades, China and India have grown to account for over half of the international student population in the U.S. This shift is due to the rising incomes of middle classes in these countries and the opportunities that U.S. universities provide.

Students in China and India now have other options. While the U.S., UK, Canada, and Australia remain top destinations, countries such as the Netherlands and South Korea are increasingly appealing. Furthermore, China is working to attract more foreign students. In 2000, the U.S. hosted about 26% of all international students; that figure has now dropped to approximately 16%.

How universities came to be — and why they are in trouble now

In a bid to meet the growing global demand for education, universities have also established satellite campuses in foreign cities, such as New York University’s branch in Shanghai, China. These campuses provide international education without requiring students to travel abroad. In 2023–24, the UK hosted about 732,000 international students while simultaneously educating around 621,000 students abroad at its foreign institutions. “This trend might increase as students realize they can earn foreign degrees without leaving home,” suggests higher-education researcher Hans de Wit from Boston College. While these transnational programs sidestep visa challenges, they raise questions about whether the education quality remains consistent.

Opinion is divided. “If I were a student, I would choose to study at Bristol University in the UK, not in Delhi,” remarks Saumen Chattopadhyay, an economist from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. Studying abroad can also offer better prospects for emigration and international networking.

While opportunities to study abroad benefit individuals, they can drain talent and resources from less affluent countries. “This has long been seen as detrimental to human capital development in African nations,” states Jowi, who is actively working to promote intra-Africa mobility and reduce brain drain by establishing local centers of excellence at universities in Southern and Eastern Africa.

What do universities teach?

Summary:

This article explores the dynamic landscape of global higher education, which hosts 264 million students. It highlights the rapid growth of student enrolment, especially in developing nations, and the rising trend of international student mobility. As Western countries become less welcoming to international students, many are seeking education elsewhere. The article also emphasizes the challenges of maintaining quality as access to higher education expands, alongside the shifting geographical preferences of students pursuing learning opportunities abroad.